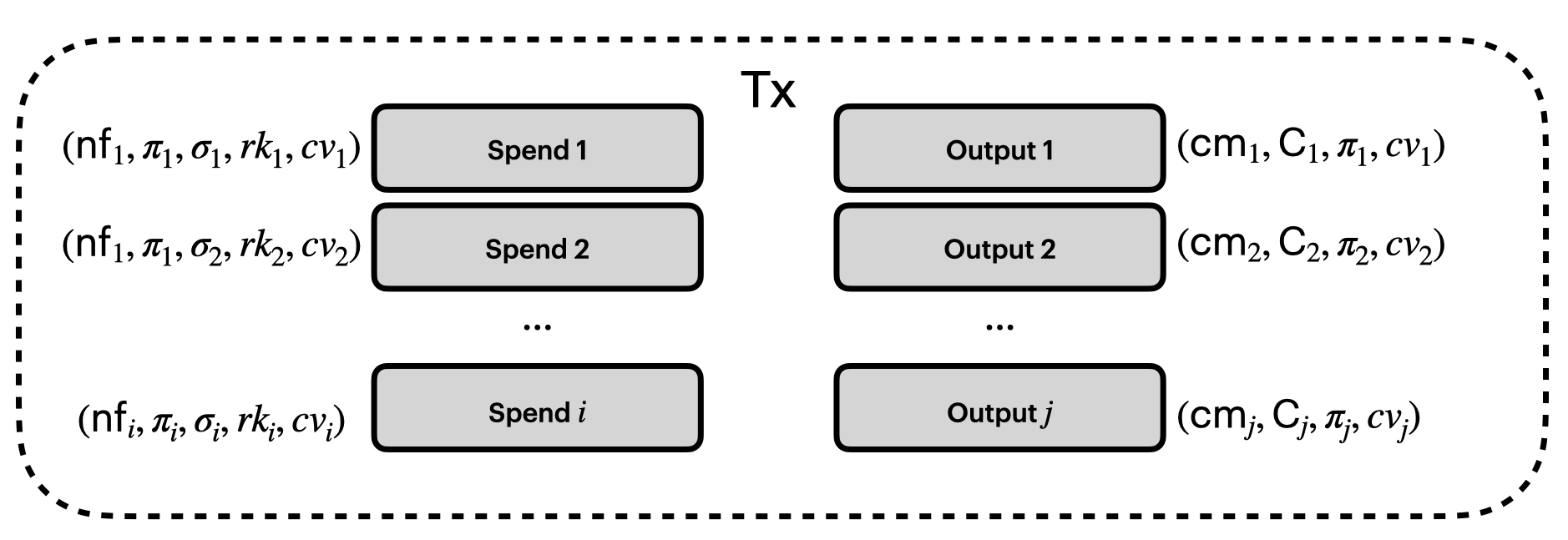

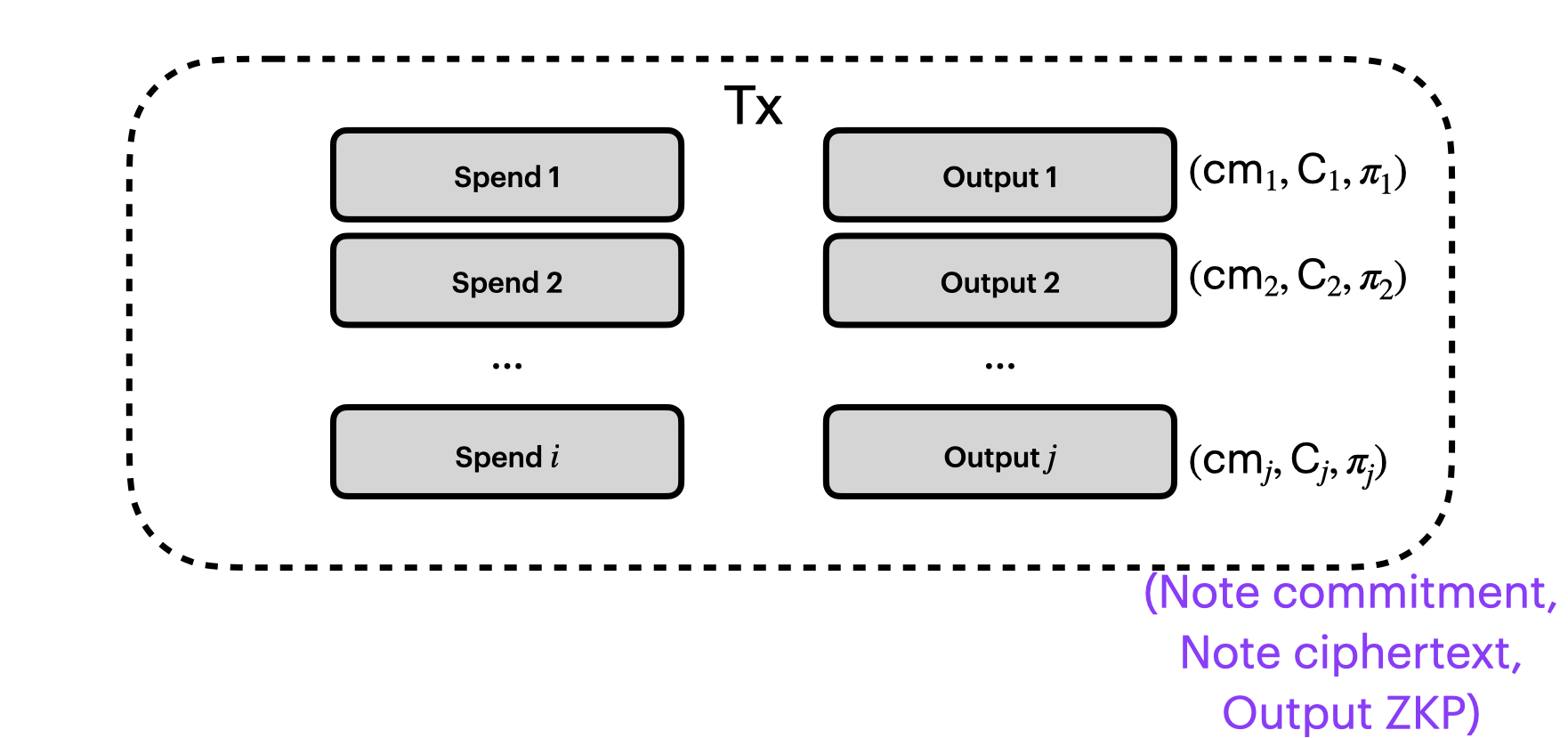

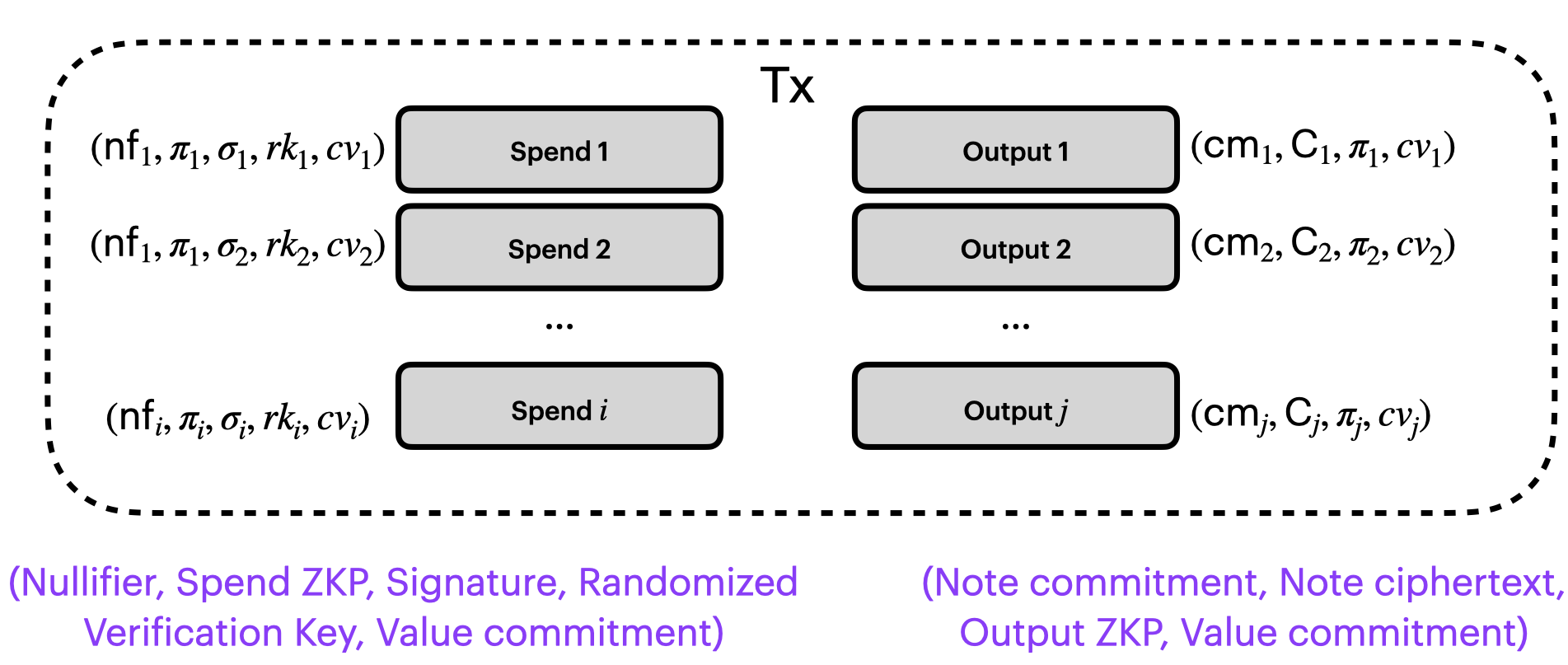

This post is a gentle introduction to shielded transactions, as used in private payment systems such as ZCash, Penumbra or on top of any Bitcoin-shaped (i.e. UTXO-based) protocol. At the end of this post, this figure will mean something to you:

But there's a lot there, so let's break it down.

Motivation: Bitcoin is not private

As you probably know, Bitcoin is peer-to-peer electronic cash. It's non-custodial: I don't need to trust a third party to hold my keys or my money. It's decentralized, in that there is no single point of failure: I don't need to trust a small subset of nodes or a single node is behaving honestly. These are great properties, and we want to preserve them.

However, Bitcoin achieves these properties at the cost of privacy. Every Bitcoin transaction is recorded on the blockchain, and is visible to everyone. It's "twitter for your bank account".

While Bitcoin is pseudonymous - using public key hashes instead of real names - this is not enough to provide privacy. This pseudonymity is easily broken: firms like Chainalysis and others make a business out of de-anonymizing bitcoin users, connecting pseudonymous bitcoin addresses to real-world identities.

These firms make use of the fact that the Bitcoin blockchain provides:

- the clear plaintext value of the transaction, e.g. 1 BTC

- the pseudonymous recipient identity, i.e. the recipient is identified by a hash of their ECDSA public key

A passive observer can use this information about the transaction graph of money flows to deanonymize users.

If you believe that privacy in an open society requires anonymous transaction systems, then you'll be happy to hear that there are solutions!

What do we want? Privacy with integrity

We want a cryptocurrency that is private, so ideally we want one in which a passive observer cannot learn anything about values, sender or recipient identities.

But, we also need to enforce all the integrity properties that Bitcoin provides. We need to ensure properties like:

- You cannot spend coins that don't exist

- You cannot double-spend coins

- You cannot spend other people's coins

- You cannot create or destroy value

What's the problem? Why is this so hard? Let's take a step back and recall how Bitcoin does any of this.

Recap: Bitcoin transaction structure

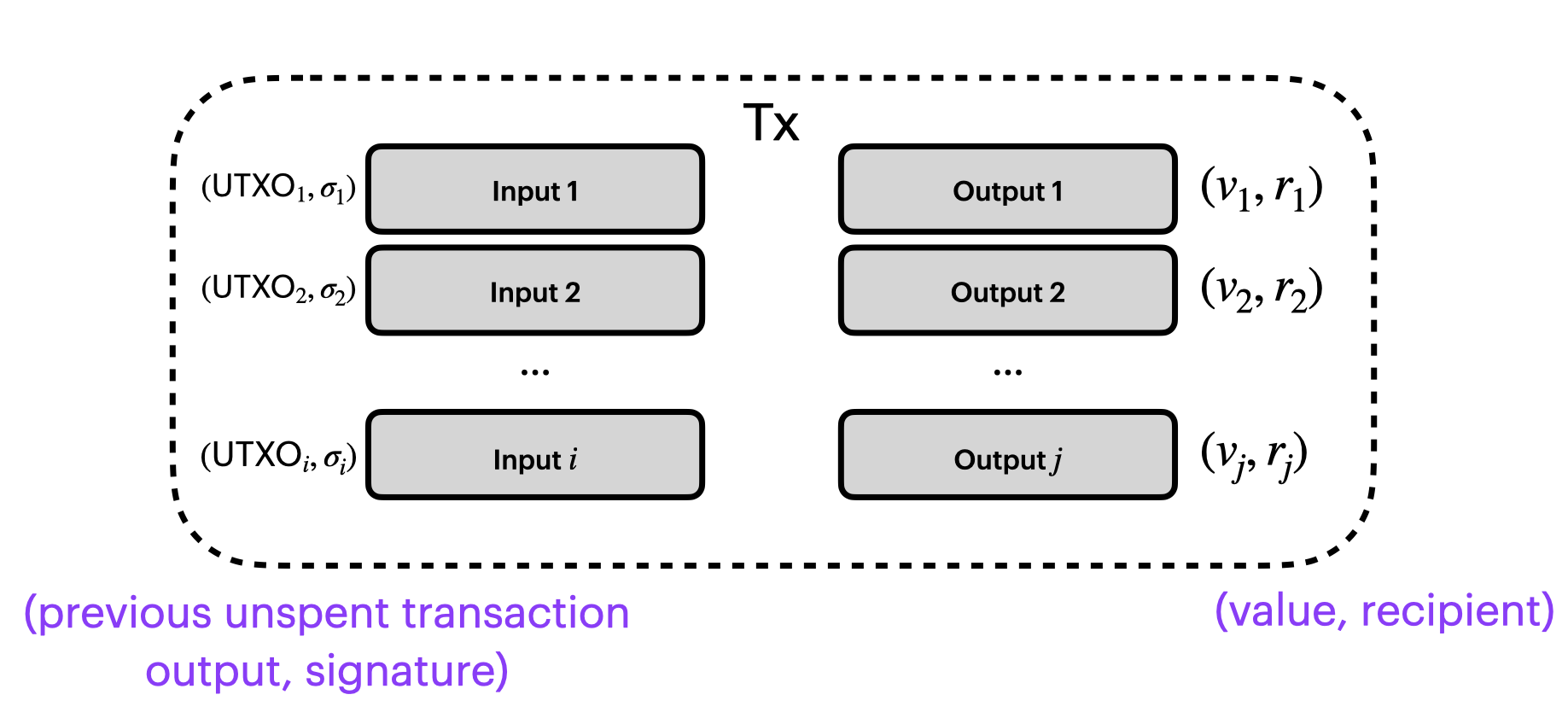

How does a Bitcoin transaction work?

Above is a simplified diagram of a Bitcoin transaction - at least the parts we need to care about.

We have a list of $i$ inputs on the left, and $j$ outputs on the right.

Outputs

Let's start at the right, with the outputs.

Each output has:

- a value $v$ and

- a recipient, identified by a public key $r$.

Technically the recipient is a specification in Bitcoin script, but we'll ignore that as it's not important for our purposes. All we need to know, is that in the simple payments case, the specification is just saying: "hey, here's the public key of the recipient, and in the future, they need to present a valid signature $\sigma$ that is verified using this public key $r$ in order to spend this output".

Inputs

Now the inputs.

The inputs each reference a previously Unspent Transaction Output (UTXO). Each UTXO has a certain value associated with it. Each inputs unlocks the value in that UTXO by presenting a signature $\sigma$ that can be verified using the public key of the recipient $r$ in the UTXO.

Integrity

Now, let's think back to our desired system properties. We already know Bitcoin doesn't provide privacy, but what about the integrity properties we enumerated above? How does Bitcoin achieve these integrity properties?

1. You cannot spend coins that don't exist

Every spend (input) references a UTXO. Nodes scan and check that the referenced UTXO exists, else they reject the transaction.

2. You cannot double-spend coins

When we reference a UTXO in an input, nodes will also scan and check that the referenced UTXO has not been spent before. Each UTXO can only be spent once. If a UTXO has been spent, the node will reject the transaction.

3. You cannot spend other people's coins

When we spend a coin, i.e. reference a UTXO in an input, we include a digital signature $\sigma$, signed with our private key. This signature is a bit of data that lets anyone in possession of our public key verify that this is my coin. Nodes are going to reject any attempt to spend a coin that you don't have authorization to spend.

4. You cannot create or destroy value

As we've established, the values in each transaction are in plaintext, so we can simply calculate that the sum of the inputs equals the sum of the outputs (modulo fees, which we'll ignore here). This ensures that no value is created out of thin air.

Properties of a private cryptocurrency

Now, let's think about what needs to change to achieve privacy. We're going to continue to use a Bitcoin-shaped protocol, and we'll use the term "coins" and "UTXOs" interchangeably.

Privacy

We want to ensure that a passive observer cannot learn anything about the value, sender or recipient identities.

We'll do that by simply encrypting all those fields. There are some details to work out, but we'll stick with the naive idea of encrypting all the data in the transaction.

Integrity

How does this impact the integrity properties we enumerated above?

1. You cannot spend coins that don't exist

Here we have a problem: we established that an observer such as a node won't have access to the transaction graph of money flows, so we can’t have nodes check references to UTXOs in the transaction graph. We need another way to check that the referenced UTXO exists.

2. You cannot double-spend coins

This is the same problem as for spending coins that don't exist: we can't check references to UTXOs in the transaction graph.

3. You cannot spend other people's coins

We definitely need a way to authorize the spending of coins, so we still need to use digital signatures. But we have a problem, because naively using digital signatures like Bitcoin introduces a privacy issue.

If I want to find what my friend Jim is doing on the blockchain, well, I have his public key, because it’s public. So I can trial verify each signature on each spend of a UTXO, and if the signature verifies, I’ve identified Jim’s spends. That violates the privacy property. We’re not supposed to be able to learn anything about Jim’s behavior.

So, we need to do something different.

4. You cannot create or destroy value

We can’t check the value balance in a transaction by naively summing up the values of the inputs and outputs, because the values are encrypted.

Building a private and decentralized UTXO-based protocol

We need to find a way to encrypt the values, sender and recipient identities, while still being able to do the integrity checks we described above.

This is a problem that researchers have been working on for over a decade. The first paper tackling this problem, Zerocoin, succeeded in creating a decentralized payments system unlinking transaction origin from sender. However, it does this with fixed size coins.

Zerocash, a followup paper, improved on this scheme. It introduced a decentralized anonymous payment scheme where sender, recipient and amount are hidden - and their scheme also allows for variable amounts. This ultimately evolved into Zcash, and we're going to roughly describe the ZCash sapling protocol design in the rest of this post.

What we're going to do is walk through each of the informal privacy and integrity properties we've been describing, and see how shielded transactions like those in Zcash (or Zcash-derived protocols) achieve them.

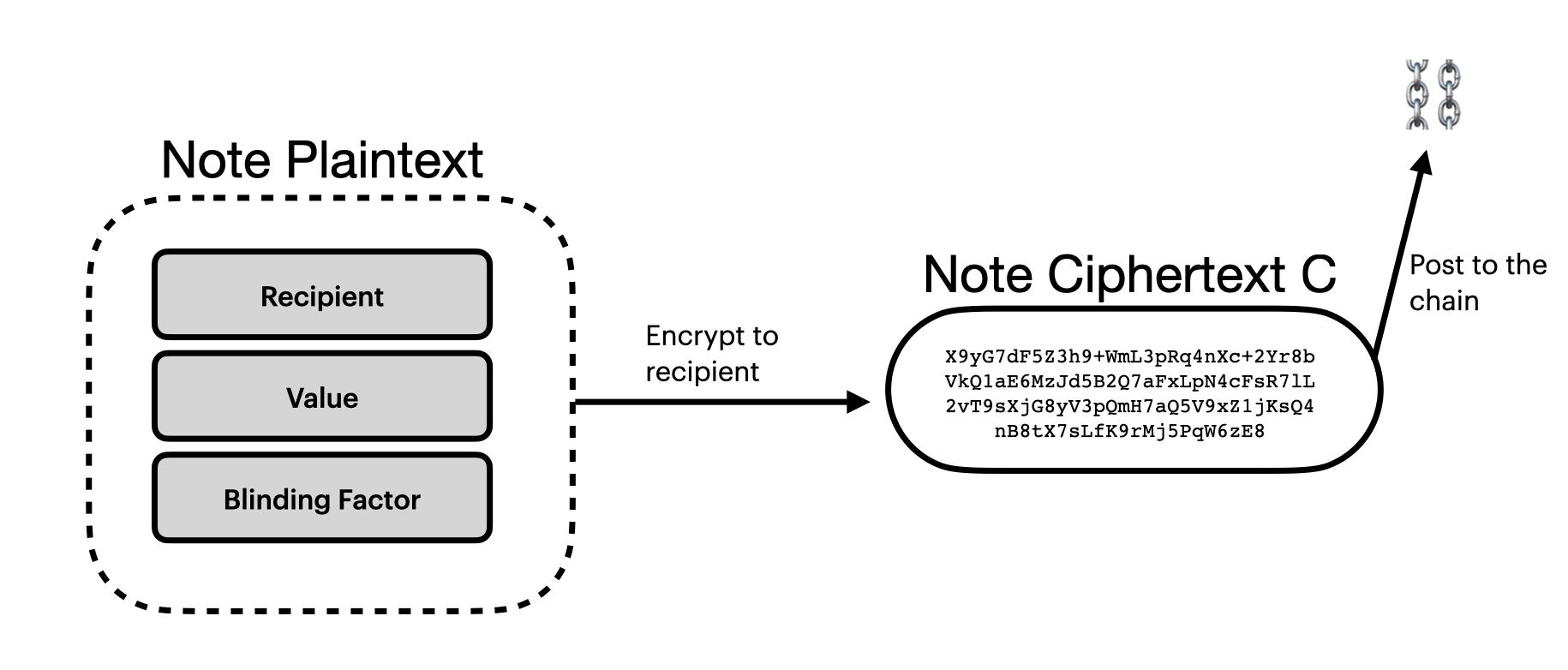

Privacy

We’re going to carry value in notes. A plaintext note consists of at least:

- a value $v$,

- a recipient $r$ (i.e. an address),

- a bit of randomness we'll call a "blinding factor" that we'll need later.

Notes are going to be encrypted and then posted on chain as part of a transaction.

Each note is going to be used only once. It gets minted, then it is spent, and then it is no longer valid. When you spend a note, you release the value of that note into the transaction which can then be used to mint other notes. This is very similar to the UTXO model of Bitcoin: each UTXO can only be spent once, and when it is spent, the value is released into the transaction.

Key Hierarchy

One interesting feature of ZCash-style cryptocurrencies is that there is a separation of capabilities in the key hierarchy.

In general, we have a spending key $sk$, that lets us spend coins, and a full viewing key $fvk$, that lets us view our part of the transaction graph.

When we sync the blockchain, we'll need to trial decrypt each note ciphertext with our viewing key to see if it decrypts to a valid note. If it does, it's a note intended for us, and one that we can spend using our spending key.

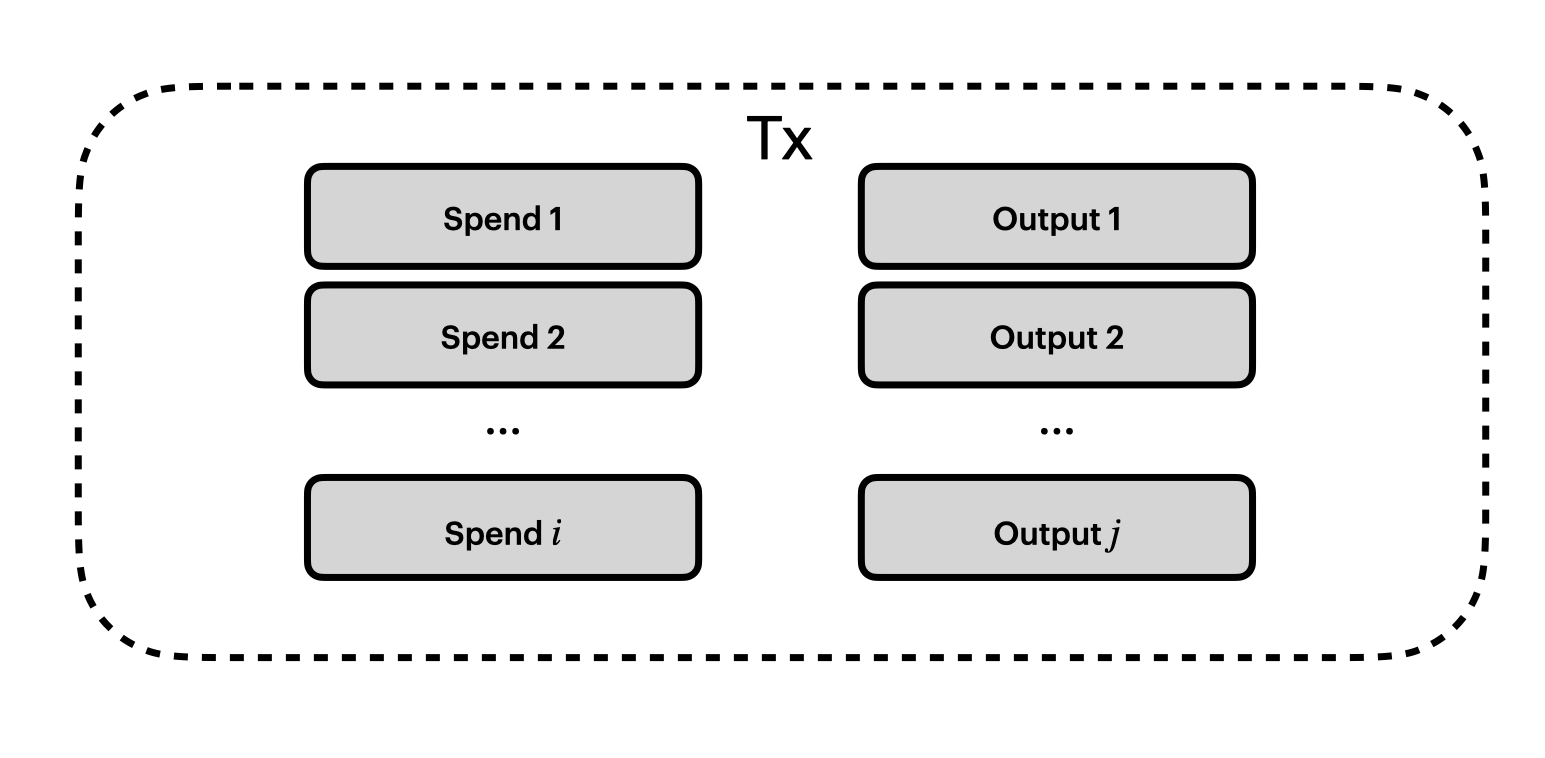

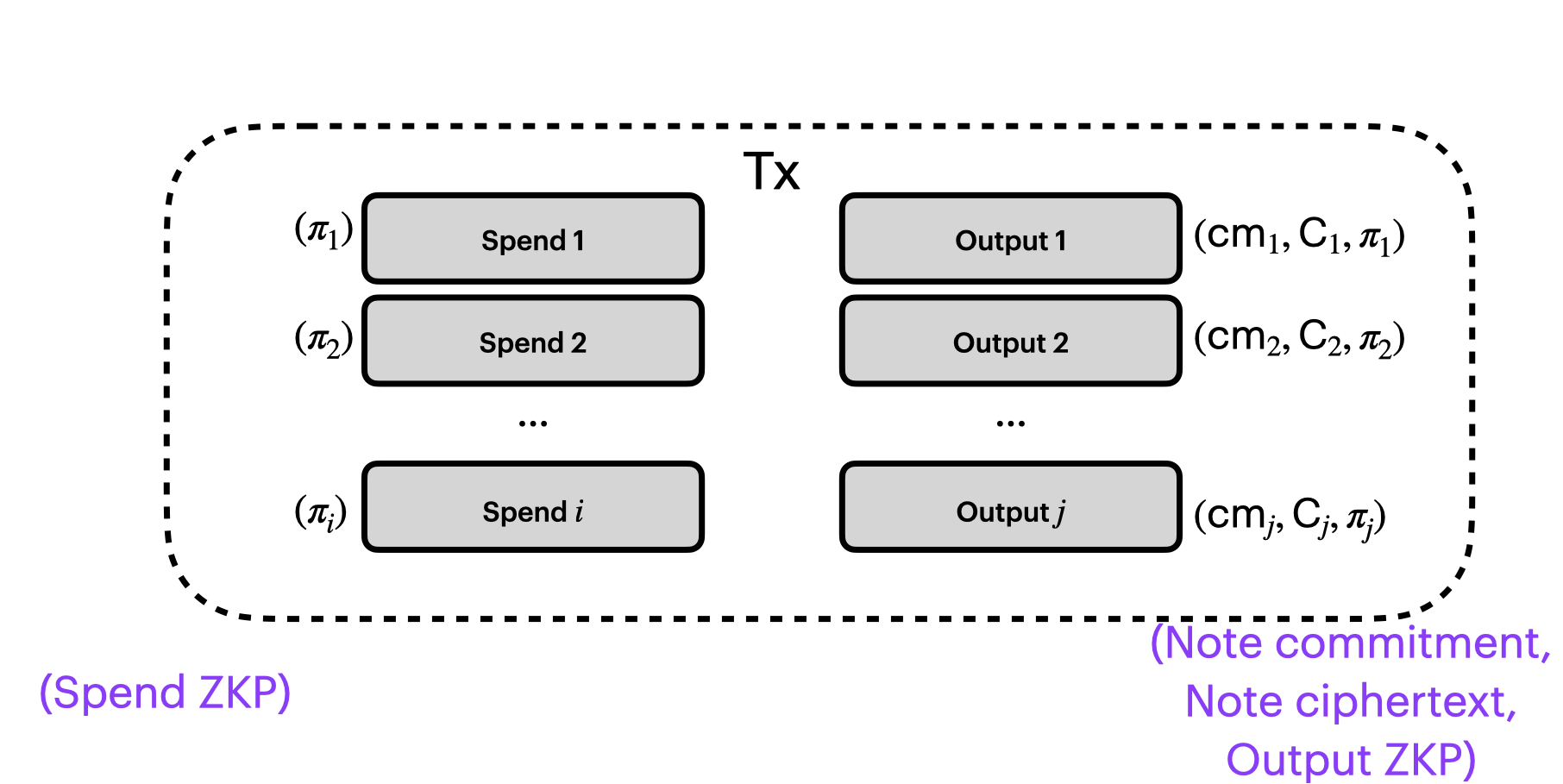

Shielded Transaction Structure

Transactions consist of multiple actions.

There are two types of actions we’re going to discuss in this post: inputs/spends and outputs. We'll call a Bitcoin-style input a spend, since that's a better name anyway.

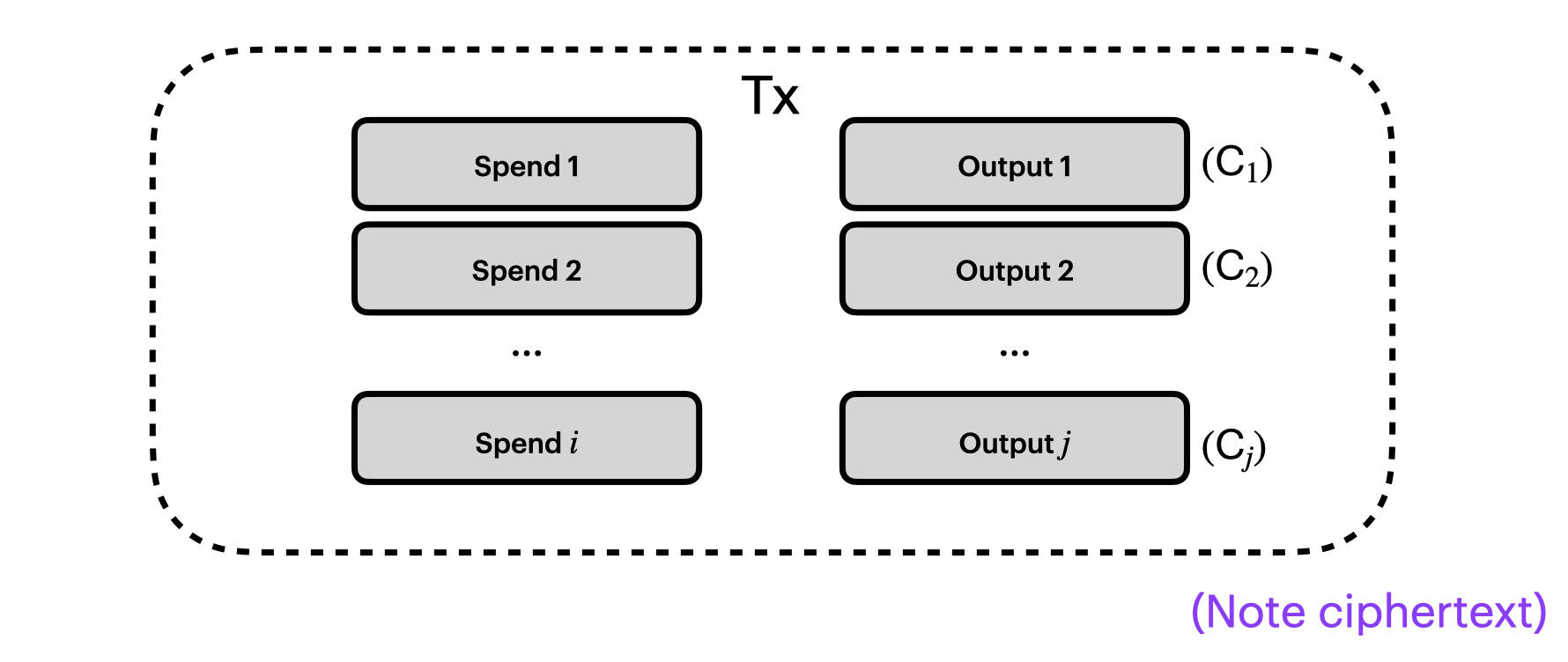

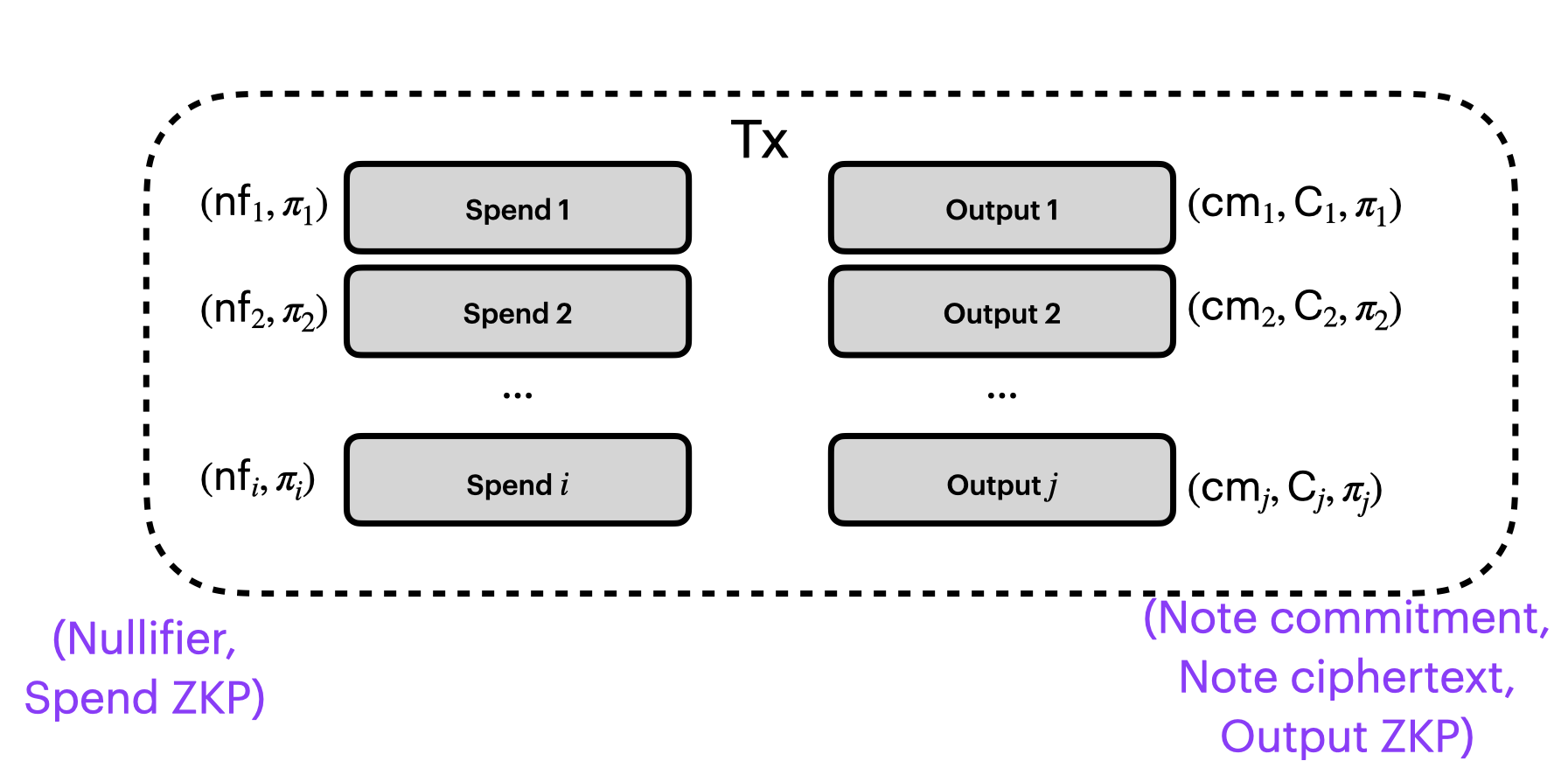

So far, our picture of a shielded transaction looks like this:

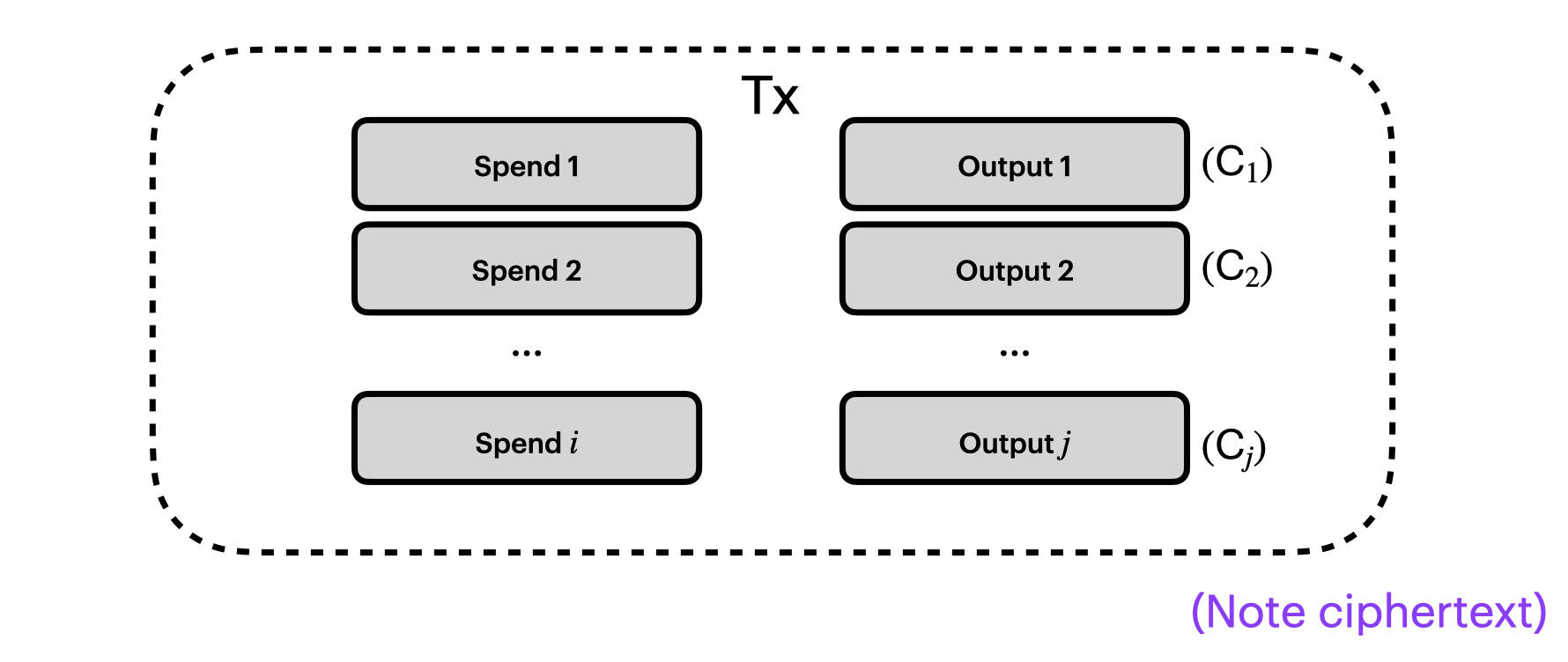

We also know that our outputs are creating a new note, encrypting it to the recipient, and posting it to the chain as a note ciphertext $(\textbf{C}_j)$. Let's add that to our picture:

Great. Let's see what other pieces we need to add to our picture.

Integrity

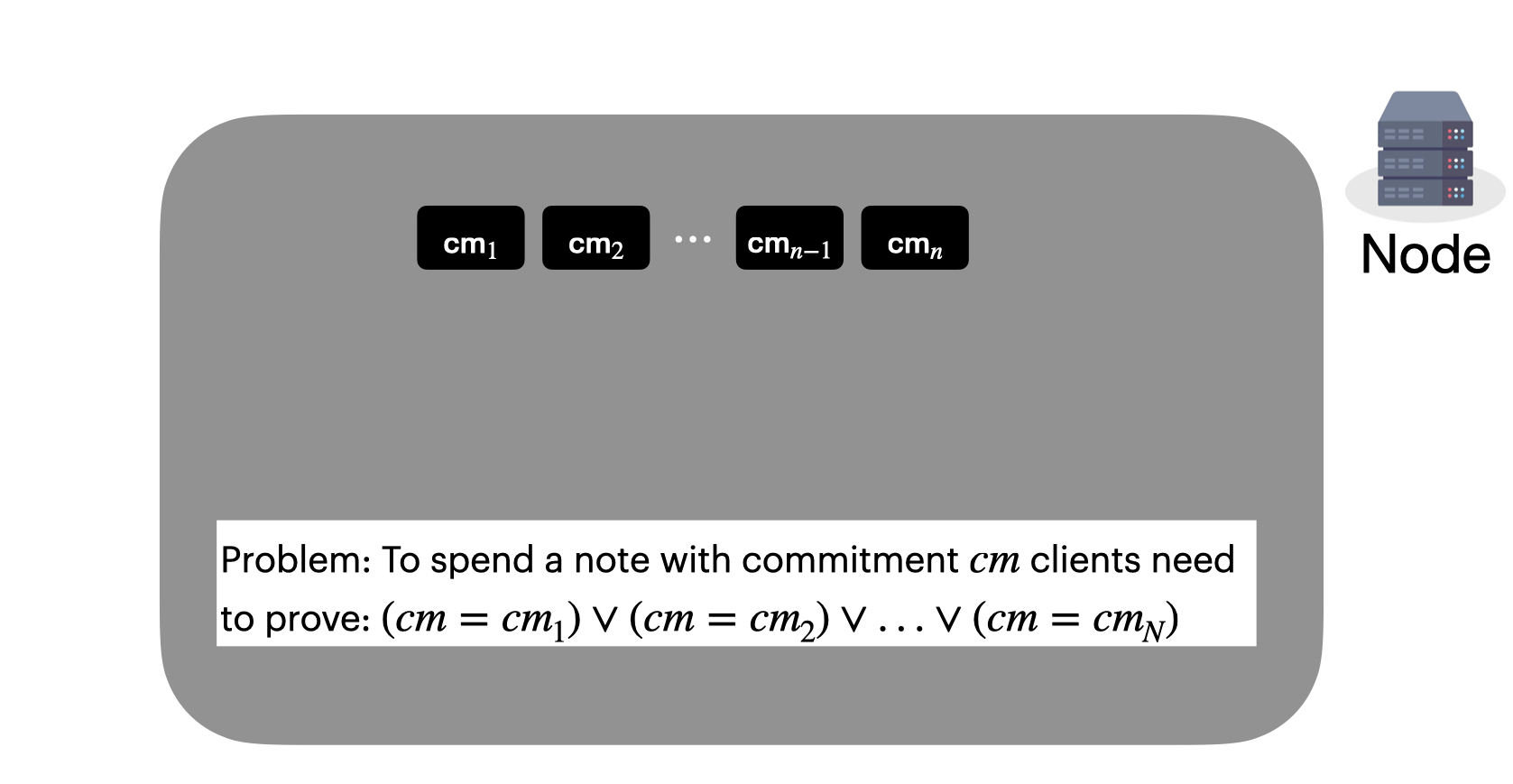

1. You cannot spend coins that don't exist

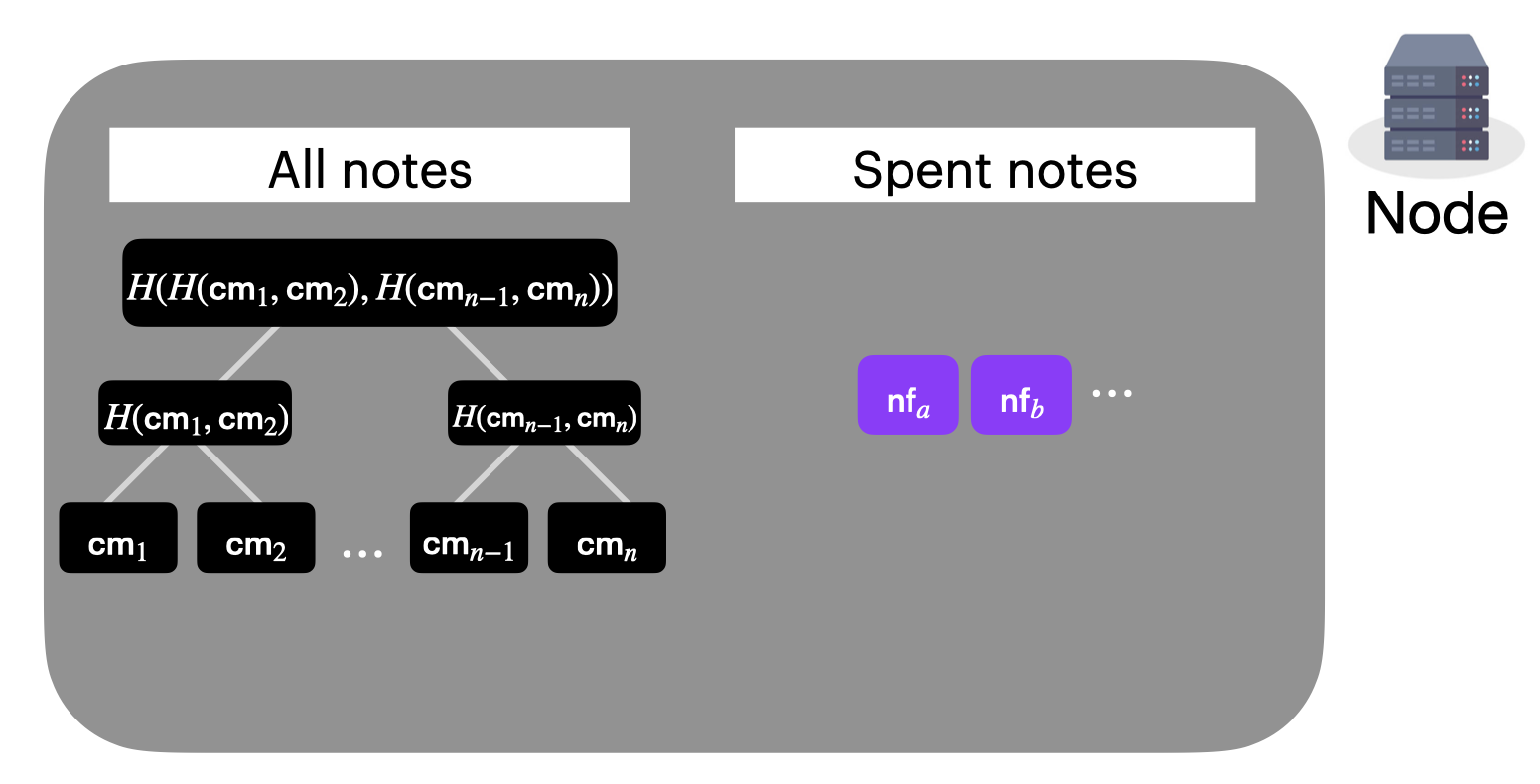

To validate transactions, we somehow need nodes to keep track of two data structures: 1. All notes that exist in the system 2. All notes that have been spent in the system

We need to do this in such a way that an observer (including the node) cannot map items in data structure 1 — all notes in the system — to items in data structure 2 — all notes that have been spent in the system. If nodes could do that, we've got the transaction graph of money flows again, and avoiding that was the whole point of this exercise!

We are going to instead derive a quantity from each note that:

- Binds us to the value $v$ and recipient $r$

- Hides the value $v$ and recipient $r$

This is exactly what we get from the binding and hiding properties of a cryptographic commitment scheme. This is also why we needed the blinding factor in our notes: it is used for generating the note commitment.

Nodes are going to store in a special data structure a cryptographic commitment to every single note that has ever existed in the system. We'll discuss later what this data structure is.

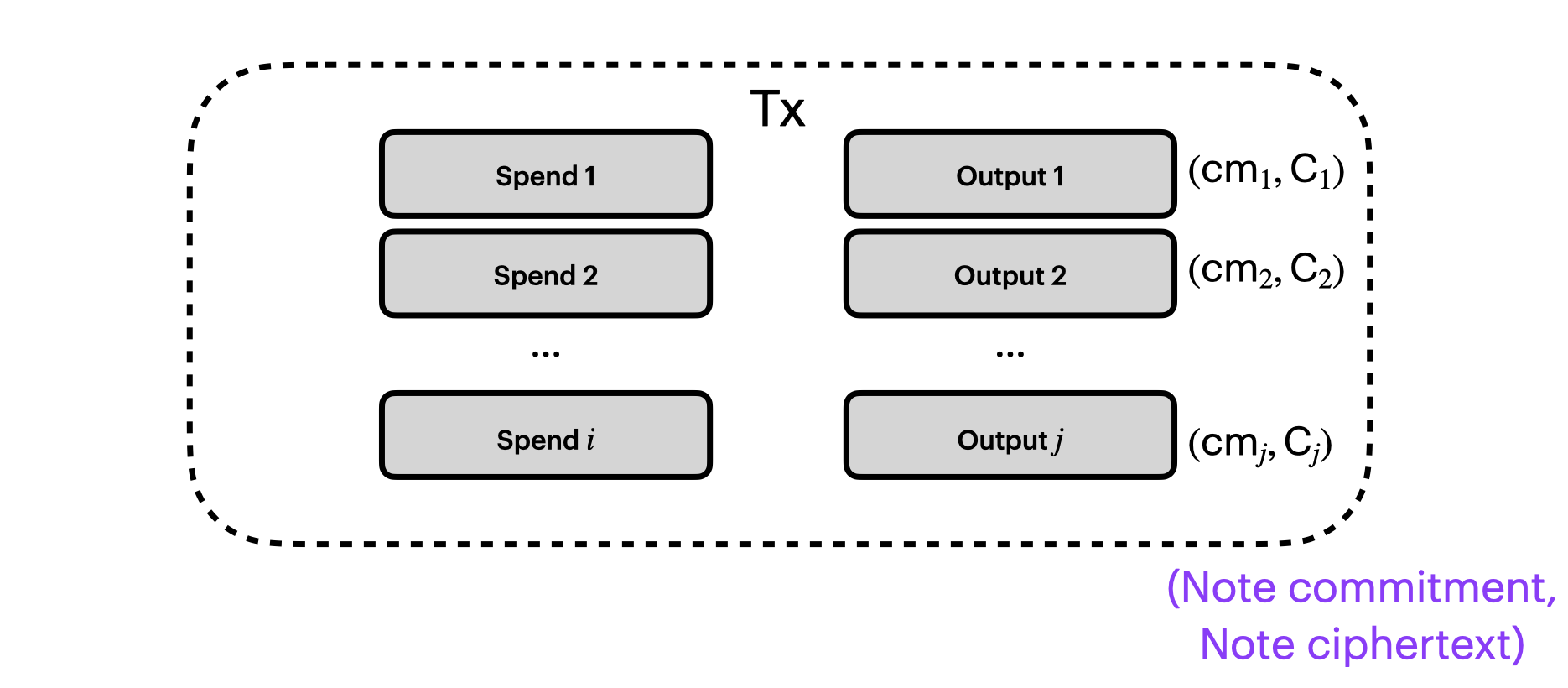

Thus far, we just had our outputs each with a note ciphertext $(\textbf{C}_j)$:

We'll also add a cryptographic commitment to each output $(\textbf{cm}_j)$. Now our picture of a shielded transaction looks like this:

The commitment is binding us to the value and the recipient in the note, such that the recipient cannot later claim “oh hey my 1 BTC note? it was actually 100 BTC”.

If a node validates a transaction, they then for each output are going to add the note commitment to a data structure that keeps track of every single note commitment in the system.

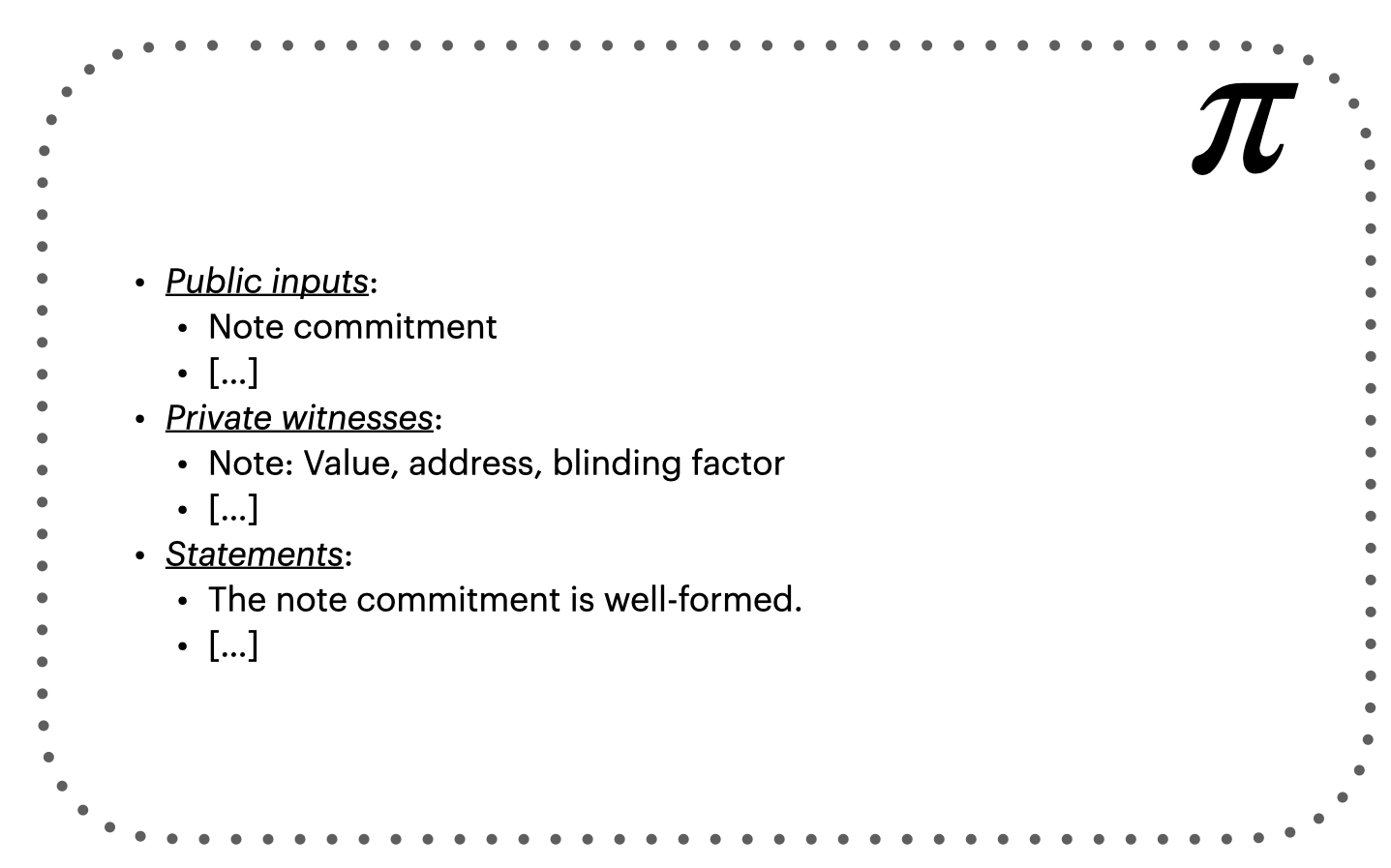

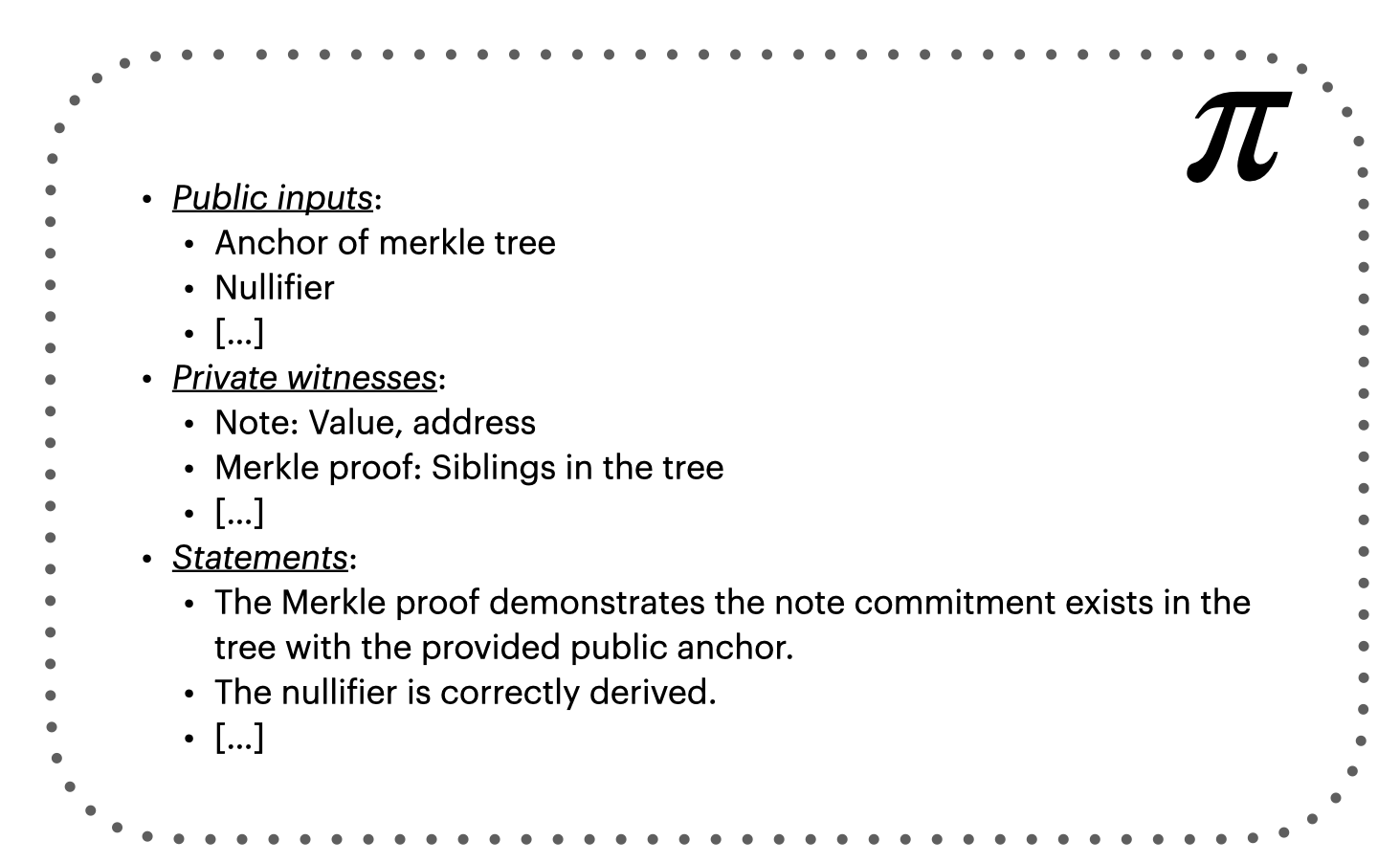

At this point, we'll need to start using Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKP). In brief, a ZKP demonstrates a particular statement is true, without revealing any information about the statement other than its veracity. In our setting, the party generating the proofs, the prover, will be the person preparing the transaction, and the person checking the proofs are valid, the verifier, will be the nodes validating the transaction. We'll be using ZKPs in various places in the protocol to make statements about private bits of data, that we'll call the "witness".

For example, for each one of our outputs, we'll need a little ZKP. This output proof $\pi_j$ is going to demonstrate that the note commitment is well-formed. We'll witness the value $v_j$ and the recipient $r_j$ in the note, and the node will verify the proof to check that the public note commitment is derived correctly.

Let's add that output proof, $\pi_j$, to our picture:

Output Circuit

One of the tricky parts about ZKPs is that proof systems require the computation or statements to be represented in a way that the proof system can understand. Typically, this is done by representing the computation as an arithmetic circuit, where the gates in the circuit are arithmetic operations such as addition. We'll need to write down as a circuit the logic that we want to prove.

Here's what our circuit will need to do at a high level (so far) for our output actions:

Nodes keep track of all notes in the system

Let's go back to how nodes are going to go about storing the two data structures: one of all notes in the system, and one of all notes that have been spent.

Well, we could just store a big list of all the notes in the system. But when we spend, we need a way to demonstrate that our note commitment is in this set. However, this is a pretty inefficient proof of size O(N) where N is the number of notes in the system. Maybe we can do better?

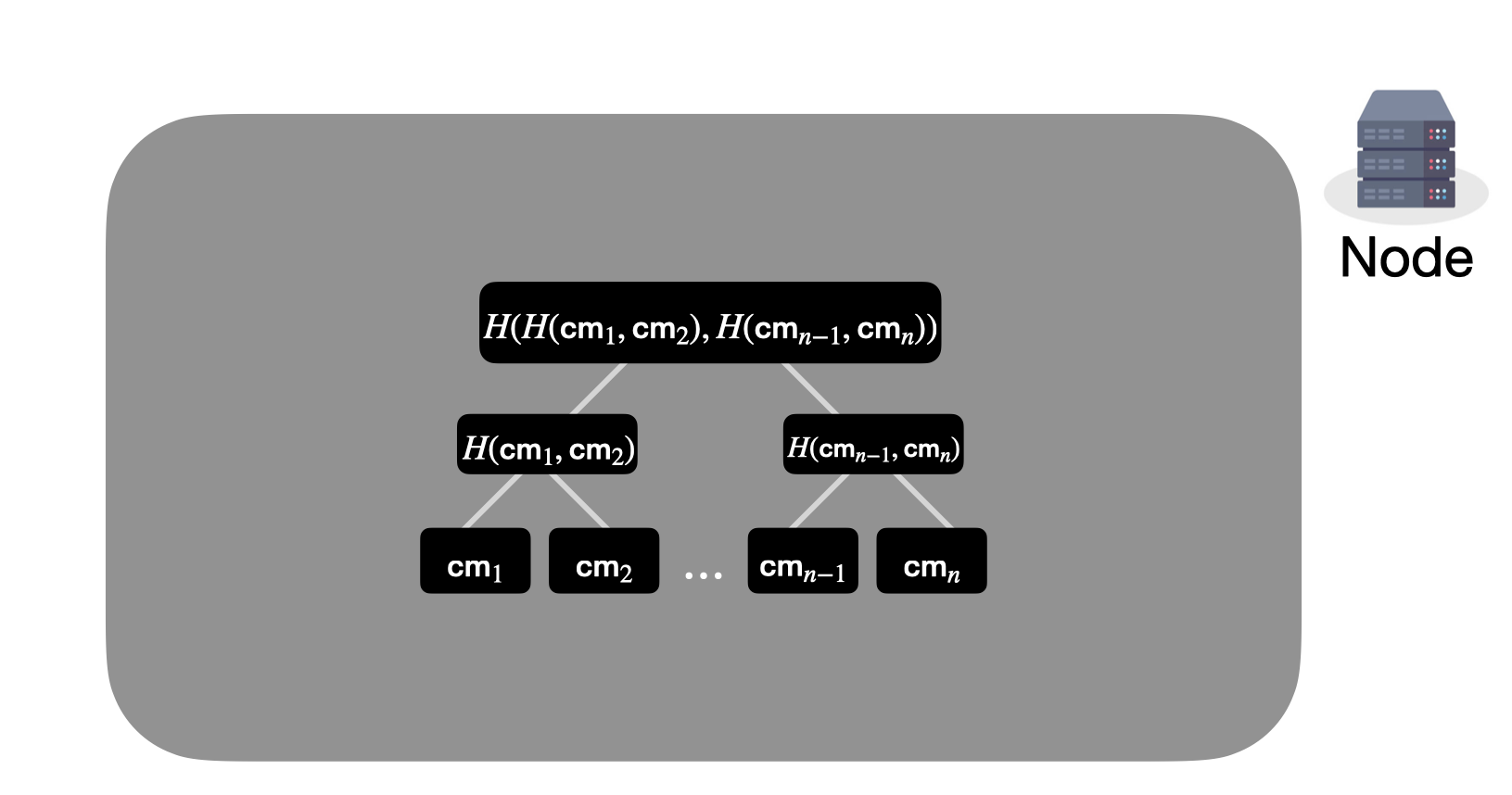

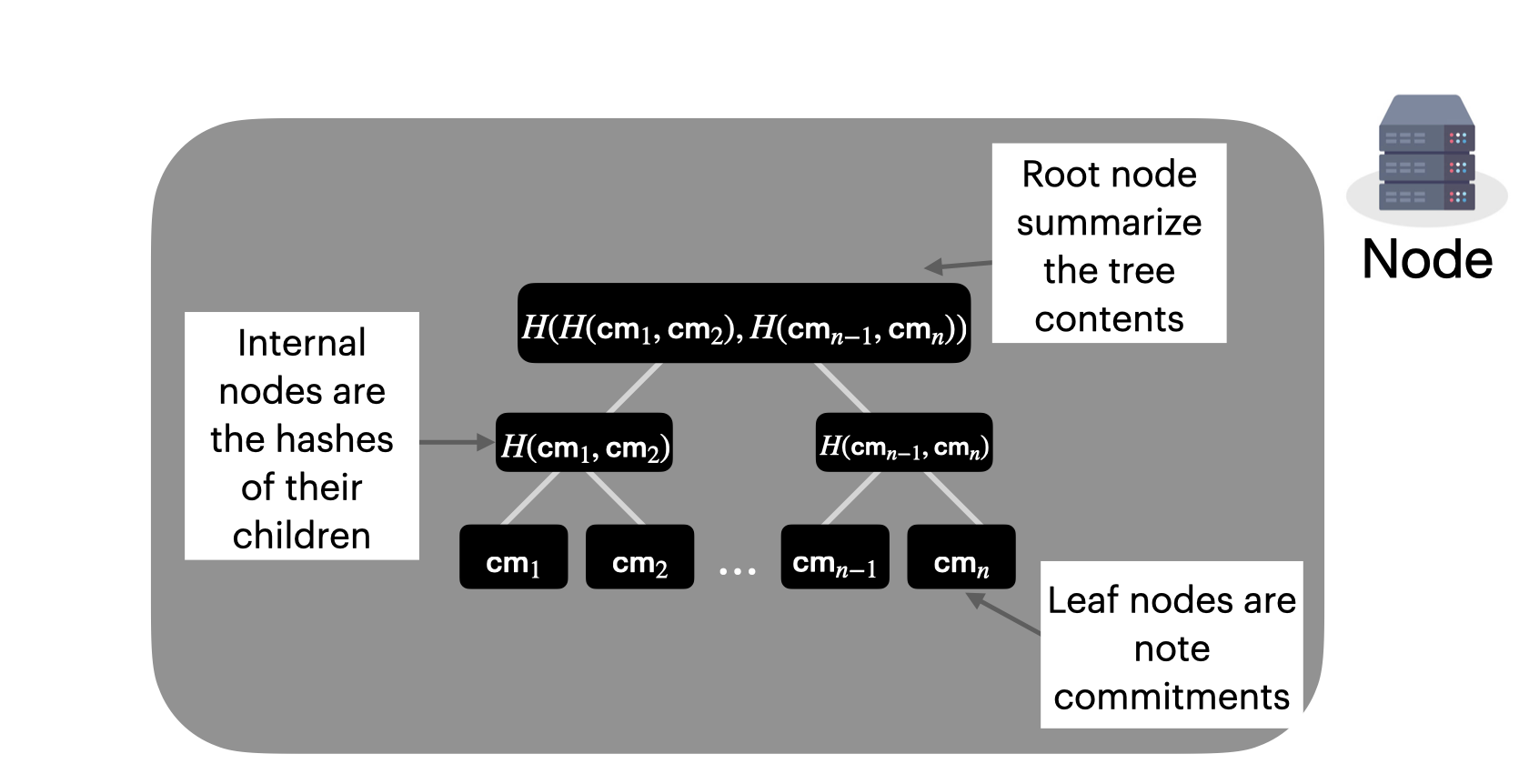

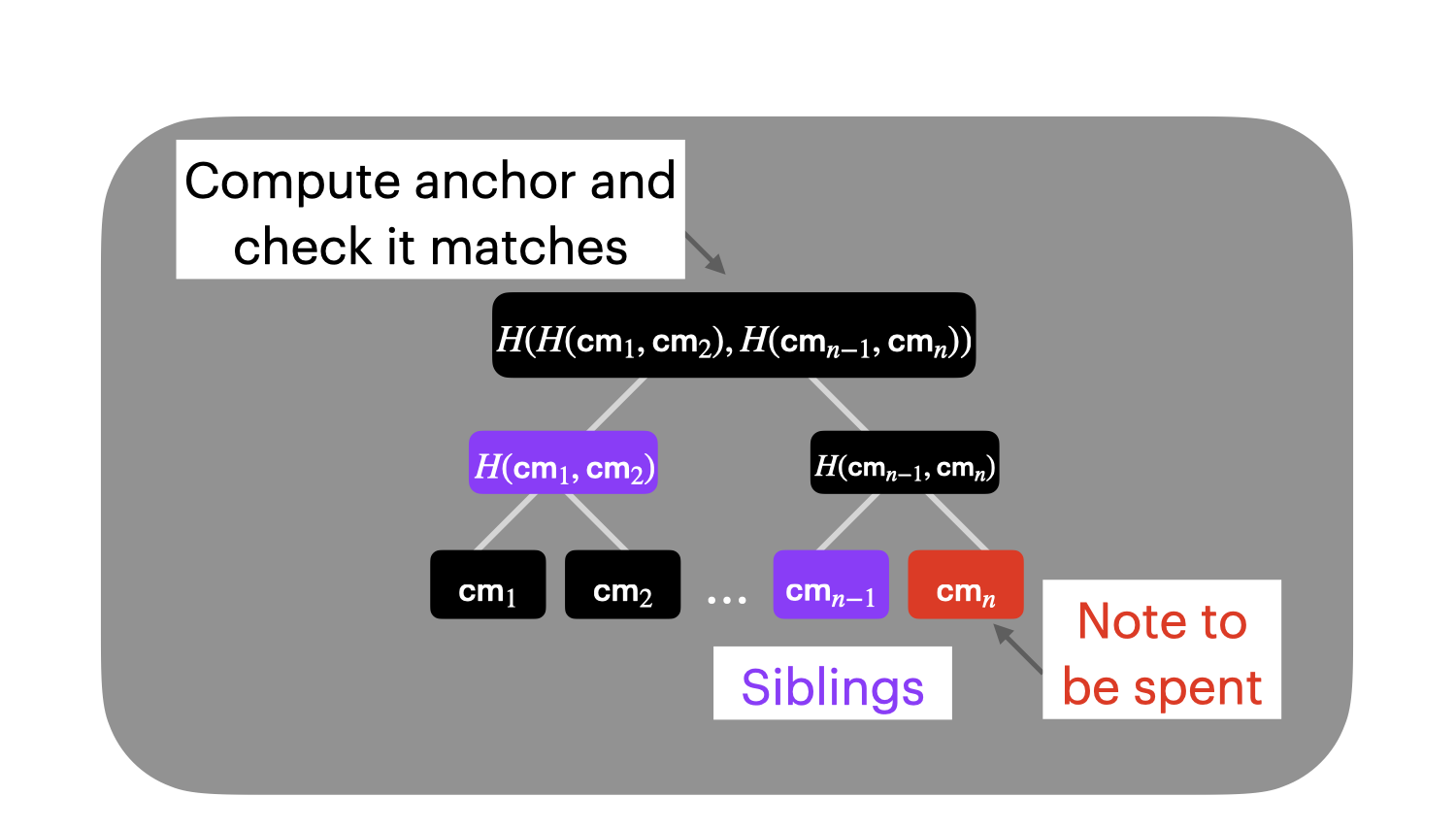

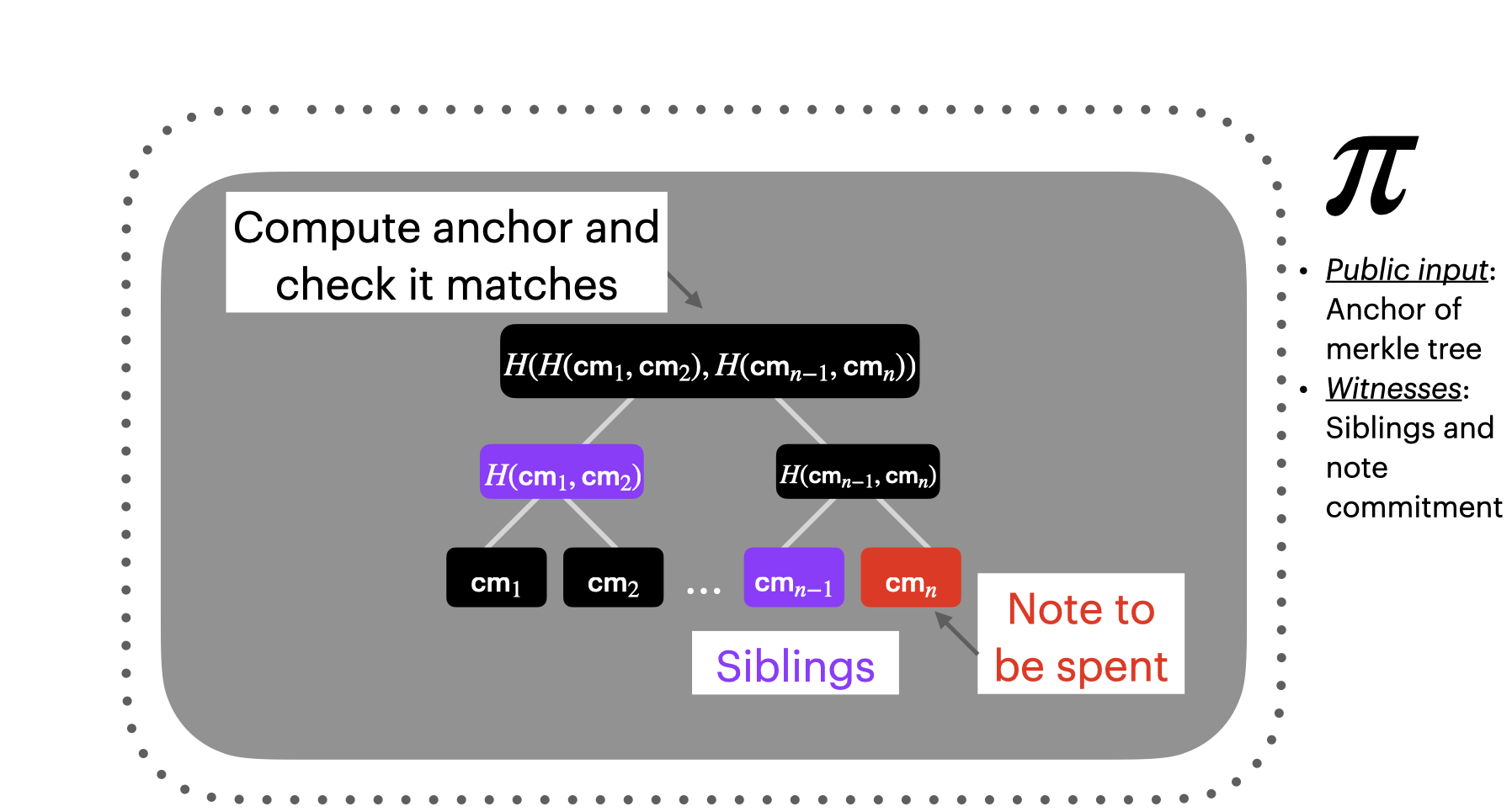

Nodes maintain an incremental Merkle tree of all note commitments

Instead, we're going to keep track of all the note commitments in the system using a Merkle tree.

A Merkle tree is simply a tree in which each internal node is the hash of its children.

We're also going to have it be append-only, and we're going to incrementally update the tree when we add notes by filling the next leaf node. Crucially, we will never delete from the tree, since that would leak information about activity on the network.

We'll have each leaf node contain a note commitment.

By using a Merkle tree, we can compress a large amount of data into a small, fixed-size value: the hash of the root of the tree, or the anchor.

Merkle proofs let us demonstrate our note is in the system

This lets us do proofs in a succinct way. We can prove set membership via a Merkle proof. We can construct a Merkle authentication path that consists of the siblings of each node on the path from our note commitment to the root of the tree. If the note is truly in the tree, when we hash together the note commitment with its siblings all the way up to the tree root, we should arrive at the public anchor.

The depth of the tree is fixed and is a constant set by the network. So the proofs are going to be the fixed-size (depth of the tree multiplied by the number of siblings), and they’re going to be small.

We do these Merkle proofs in a ZKP

But wait, we can't provide our Merkle authentication path to the node/verifier, because then the verifier can learn something about our note commitment.

So, to make these proofs private, we need to do the Merkle proof inside a ZKP.

Great. That will prove to the verifier that the note commitment is in the tree meaning that it exists in the system. And we can add a little more to our picture of a shielded transaction: the spend ZKP $\pi_i$.

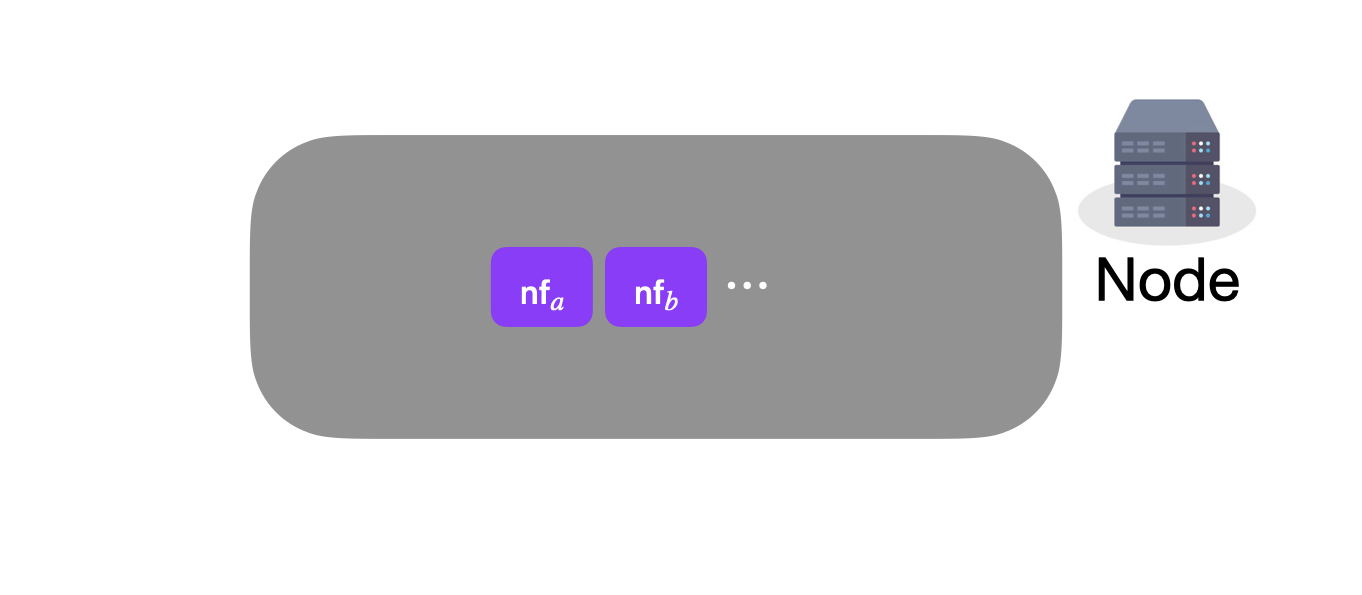

2. You cannot double-spend coins.

We've described our first node data structure, tracking all notes that ever existed in the system. What about the second data structure, the set of all notes that have been spent in the system?

For each note, we're going to define a way of deriving a special value, called a nullifier $nf$. It's effectively a serial number for the note. Critically, there can only be one valid nullifier per note. If you find a trick that lets you derive another nullifier that will be considered valid for that note, that will constitute a way to double spend.

Nodes are going to store in a second data structure the set of all nullifiers that have ever been revealed:

When we do a spend, we are going to reveal the nullifier associated with the note. Once revealed, we cannot spend the same note again.

Nodes will check as part of transaction verification that the nullifier in a spend is not in the nullifier set. If it is, the transaction is rejected.

So we're going to add the nullifier to our picture. For each spend, we reveal the nullifier $nf_i$.

Spend Circuit

We're also going to add to the spend ZKP a check that the nullifier has been derived correctly from the note being spent.

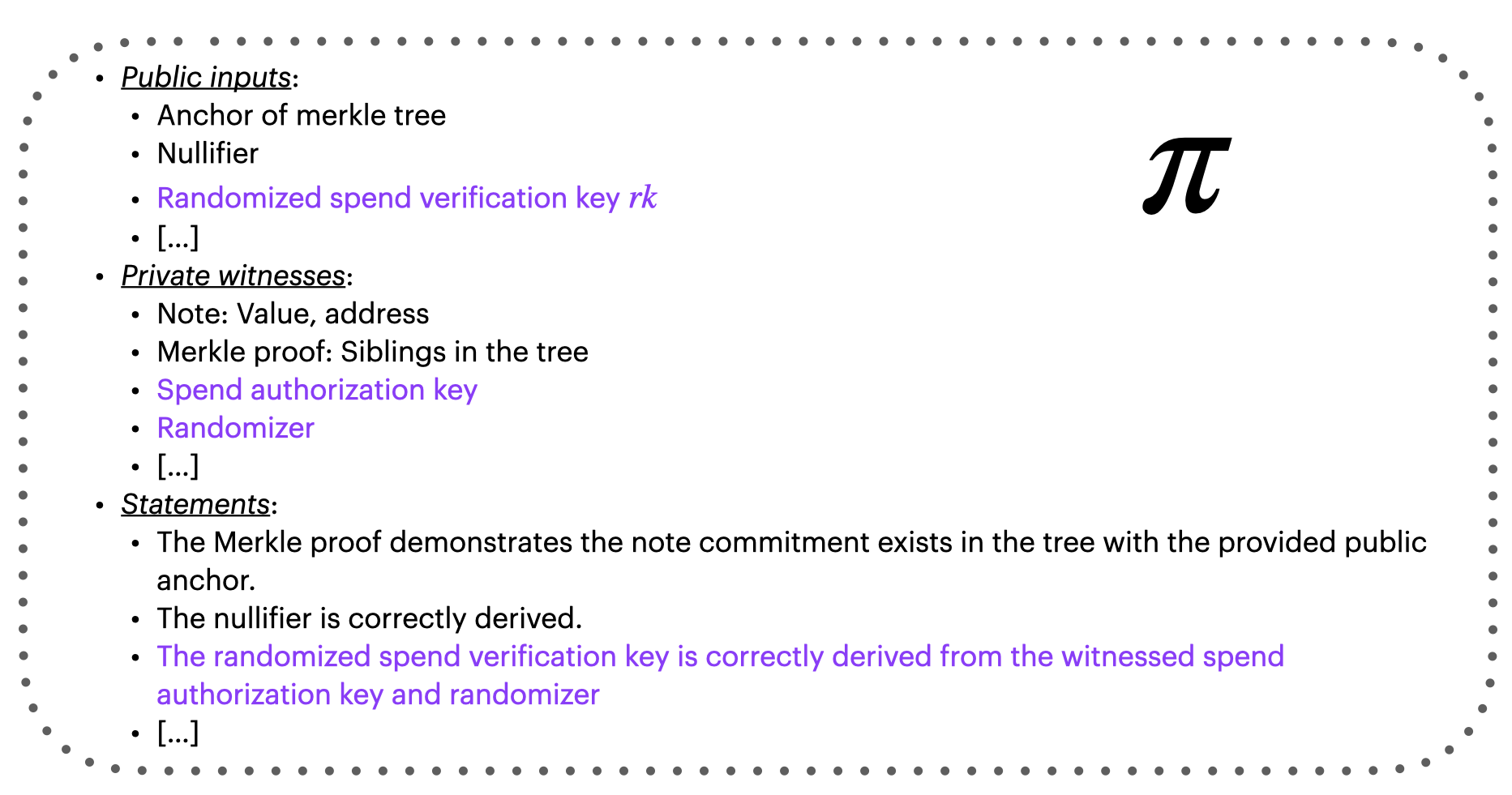

Here's what our circuit now looks like for our spend actions:

Node state management

We now have the two data structures that nodes will need to maintain:

- The incremental Merkle tree of all note commitments in the system.

- The nullifier set that corresponds to all spent notes in the system.

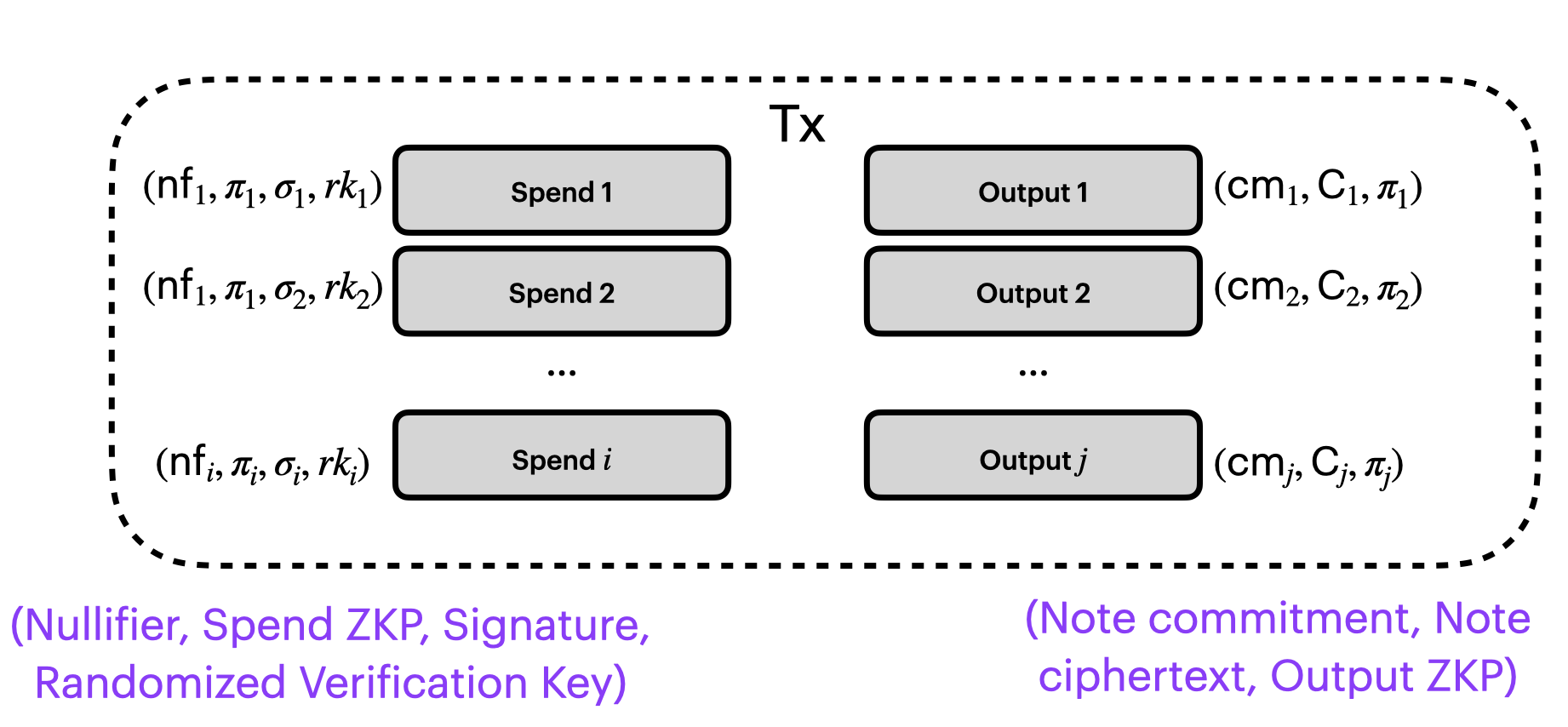

3. You cannot spend other people's coins

Recall from earlier in the post that we can't naively use regular signature schemes in privacy-preserving protocols because they leak information about the signer's identity. An observer can trivially link spends by doing trial verification using public keys of their targets.

Instead we use a re-randomizable signature scheme.

We derive a one-time use (“randomized”) key $rk$ from our real key $ak$, and use that:

$rk = ak + [\alpha]B$

We'll provide the one-time use verification key $rk_i$ on each spend:

Spend Circuit

We also need to demonstrate in our ZKP that the randomized key (public on the transaction) is a correct randomization given the witnessed real key $ak$ and randomizer $\alpha$.

Here's what our circuit looks like so far for our spend actions:

4. You cannot create or destroy value

Finally, we need to ensure that the sum of the values in the inputs equals the sum of the values in the outputs.

Here we need to take a little detour into the properties of Pedersen commitments.

Pedersen commitments are additively homomorphic.

A homomorphism is just a function between two algebraic structures that preserves their operations, meaning it keeps the structure's properties intact when applied. An additive homomorphism is a type of homomorphism that specifically preserves addition. Let's see an example to make clear how this works and how it helps us:

We have a Pedersen commitment scheme which generates a commitment $cm$ using an algorithm $\texttt{Commit}$ that takes a value $m$ and some randomness $r$ as follows:

$cm = \texttt{Commit}(m, r) = [m]G + [r]H$

G and H are going to be constants that we pick as part of the protocol.

Given that definition, let's now assume we have two commitments $cm_1$ and $cm_2$. Using the definition above we have:

$cm_1 = \texttt{Commit}(m_1, \texttt{randomness}_1) = [m_1]G + [\texttt{randomness}_1]H$

$cm_2 = \texttt{Commit}(m_2, \texttt{randomness}_2) = [m_2]G + [\texttt{randomness}_2]H$

If we add our two commitments together, $cm_1 + cm_2$, we get:

$cm_1 + cm_2$

$= [m_1]G + [\texttt{randomness}_1]H + [m_2]G + [\texttt{randomness}_2]H$

Rearranging, we get:

$cm_1 + cm_2 = [m_1 + m_2]G + [\texttt{randomness}_1 + \texttt{randomness}_2]H$

And that is equivalent to:

$cm_1 + cm_2= \texttt{Commit}(m_1 + m_2, \texttt{randomness}_1 + \texttt{randomness}_2)$

What does this mean? It means that if we have two commitments, we can add them together to get a new commitment to the sum of the values being committed to. At no point in this did we learn anything about the individual values.

Value commitments

We're going to add a value commitment which we'll call $cv$ to every single action in the transaction.

It'll be derived from the relevant note's value $v$ and a bit of randomness $\texttt{randomness}$:

$cv = [v]G + [\texttt{randomness}]H$

We'll adopt a convention where $v$ is the positive when we're doing a spend (releasing value into the transaction), and $v$ is negative when we're doing an output (consuming value from the transaction).

Let's add those value commitments $cv_i$ and $cv_j$ to our picture of a shielded transaction:

Every single action has a value commitment. And we can sum all the value commitments. If the transactino balances, then the values should cancel out: the positive value should balance with the negative value. This is done by checking that the sum of the value commitments ($\sum_{i}\sum_{j}(cv_{i,j})$) is a commitment to zero.

We'll also need to include in the transaction the sum of the blinding factors, such that we can check:

$\sum_{i}\sum_{j}(cv_{i,j}) = \texttt{Commit}(0, \sum_{i}\sum_{j}(\texttt{randomness}_{i,j}))$

And, we'll also need to include in each circuit a check that the value commitments are well-formed from the relevant note.

Summary: How Shielded Transactions Work

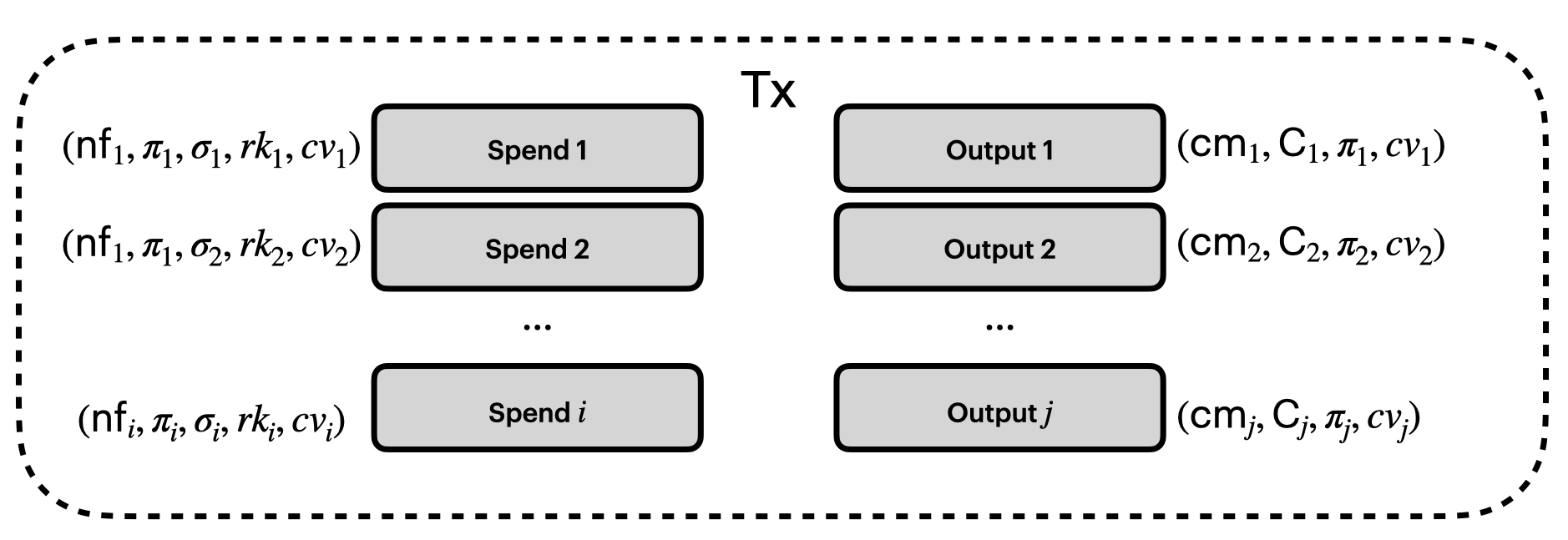

Remember that figure from the beginning? Now we understand each component of it:

In summary:

- All notes are encrypted on the blockchain: the chain never sees recipient, sender, or value.

- The note commitment tree is an incremental Merkle tree that is an append-only data store of all notes in the system.

- Spends of a note must demonstrate in a zero knowledge proof that the note commitment is in the commitment tree.

- Notes are nullified/deleted by revealing a nullifier (once, constituting double spend protection) that goes into the nullifier set. Observers cannot link nullifier to notes that were invalidated.

- Spends also must demonstrate control of the note via a randomized signature.

- Value conservation is provided through the additively homomorphic property of value commitments.

As you might imagine, there's a lot of detail that I've glossed over here. If you're interested in learning more, I recommend checking out the ZCash protocol specification.